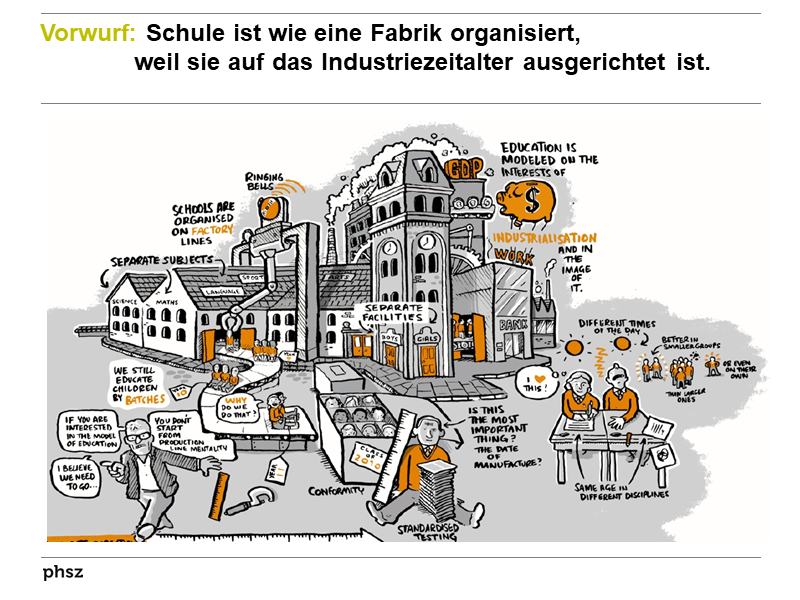

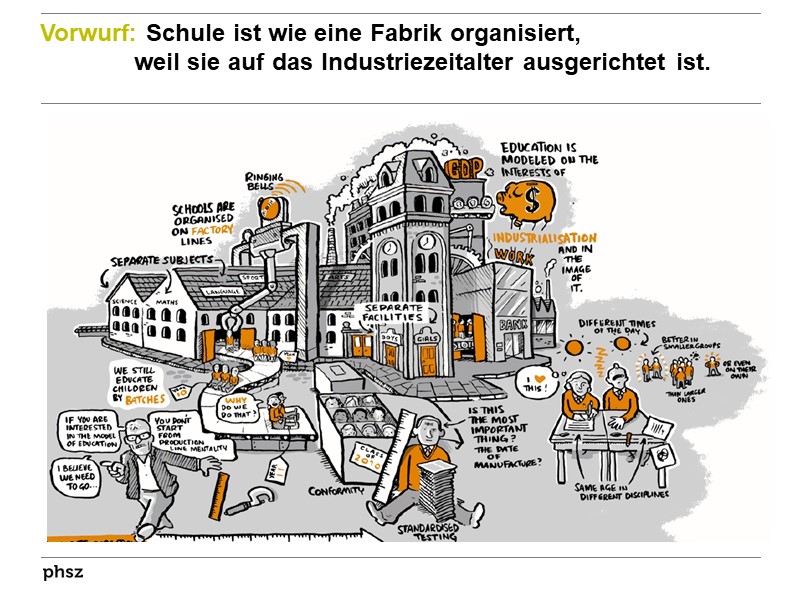

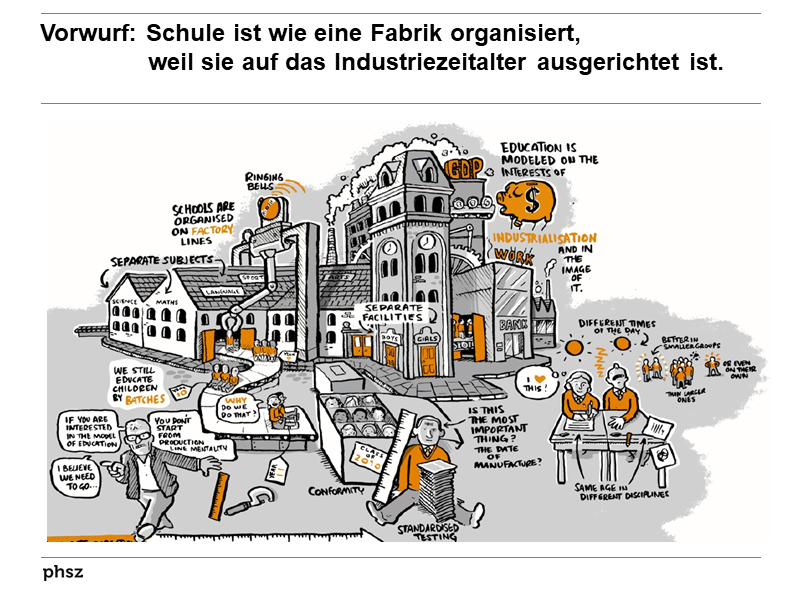

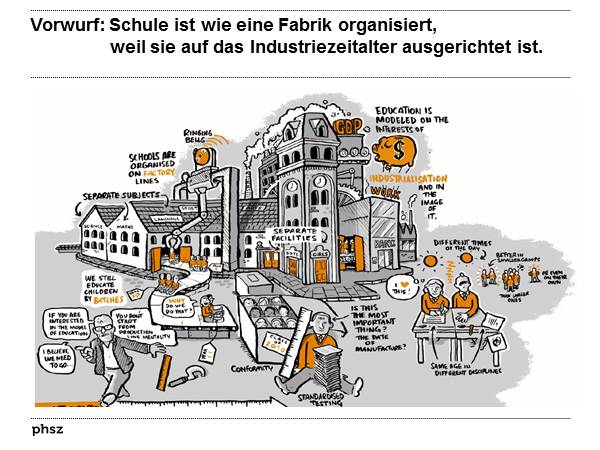

Weil die heutige Schule auf die Bedürfnisse der Industriegesellschaft ausgerichtet ist, ist sie wie eine Fabrik organisiert

Diese Seite wurde seit 9 Jahren inhaltlich nicht mehr aktualisiert.

Unter Umständen ist sie nicht mehr aktuell.

Diese Seite wurde seit 9 Jahren inhaltlich nicht mehr aktualisiert.

Unter Umständen ist sie nicht mehr aktuell.

BiblioMap

BiblioMap

Bemerkungen

Bemerkungen

ln this sense, many academics, technologists, industrialists and even some practitioners are now beginning to highlight what they see as the fundamental incompatibility between digital technology and what is referred to as the ‘Henry Ford model ofeducation’ or industrial-era’ schooling (e.g. Whitney et al. 2007). Such critiques hark back to Alvin Toffler’s depictions throughout the 1960s and 1970s of the epistemologically and technologically outmoded ‘industrial-era school`. Here Toffler (1970, p.243) decried schooling as an anachronistic by-product of ‘that relic of mass production, the centralised work place' - pointing to factory-like examples such as schools’ reliance on rigid timetables and scheduling, as well as their emphasis on physical presence and ordering of people

and knowledge. Forty years on from Toffler’s initial observations, many educational technologists continue to decry the ‘cookie curter’ industrial-era school as a profoundly unsuitable setting for the more advanced forms of learning demanded by the knowledge age and post-industrial society (e.g. Miller 2006; Warner 2006; Kelly et al. 2008).

ln this sense, many academics, technologists, industrialists and even some practitioners are now beginning to highlight what they see as the fundamental incompatibility between digital technology and what is referred to as the ‘Henry Ford model ofeducation’ or industrial-era’ schooling (e.g. Whitney et al. 2007). Such critiques hark back to Alvin Toffler’s depictions throughout the 1960s and 1970s of the epistemologically and technologically outmoded ‘industrial-era school`. Here Toffler (1970, p.243) decried schooling as an anachronistic by-product of ‘that relic of mass production, the centralised work place' - pointing to factory-like examples such as schools’ reliance on rigid timetables and scheduling, as well as their emphasis on physical presence and ordering of people

and knowledge. Forty years on from Toffler’s initial observations, many educational technologists continue to decry the ‘cookie curter’ industrial-era school as a profoundly unsuitable setting for the more advanced forms of learning demanded by the knowledge age and post-industrial society (e.g. Miller 2006; Warner 2006; Kelly et al. 2008). 5 Vorträge von Beat mit Bezug

5 Vorträge von Beat mit Bezug

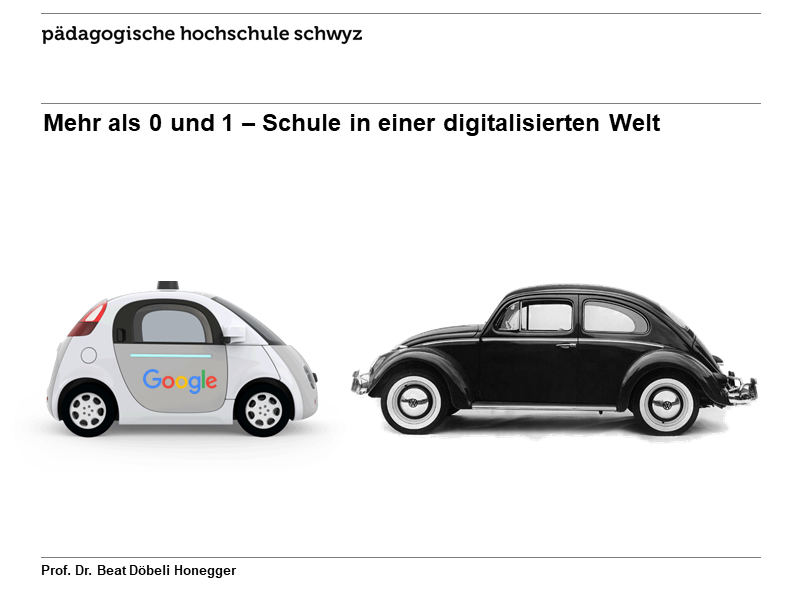

- Schule in einer digitalisierten Welt

Bildungstag Obwalden, 20.03.2015

- Dem digitalen Flächenbrand begegnen

Weiterbildungstag Primarschule Wädenswil, 07.04.2015

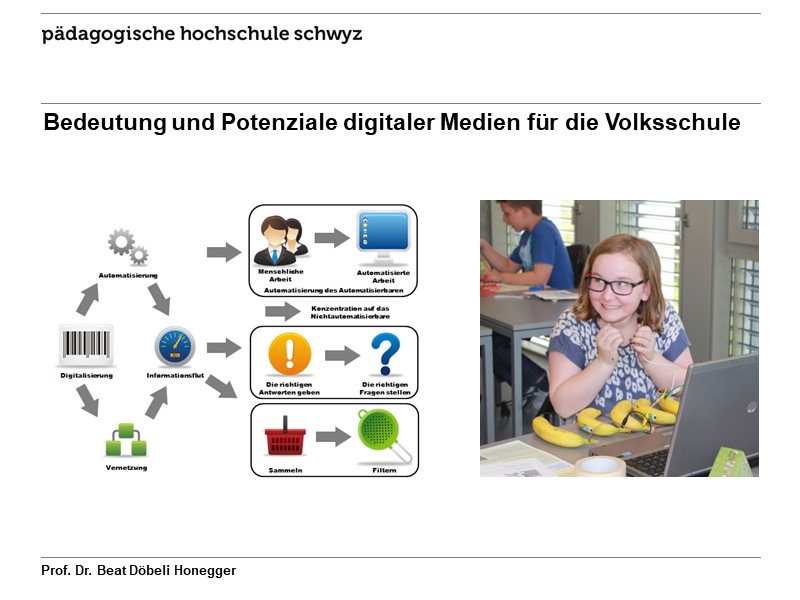

- Bedeutung und Potenziale digitaler Medien für die Volksschule

Verband Schwyzer Gemeinden und Bezirke (vszgb)

Rothenthurm, 16.04.2015

- Mehr als 0 und 1 - Schule in einer digitalisierten Welt.

Digitale Medien in der Schul- und Unterrichtsentwicklung - Herausforderung und Chance für die Bildung

Wolfsburg, 07.11.2015

- Lehren und Lernen im digitalen Zeitalter

BASPO / EHSM Magglingen, 10.03.2016

Zitationsgraph

Zitationsgraph

Zitationsgraph (Beta-Test mit vis.js)

Zitationsgraph (Beta-Test mit vis.js)

4 Erwähnungen

4 Erwähnungen

- Future Shock (Alvin Toffler) (1970)

- Schools and Schooling in the Digital Age - A Critical Analysis (Neil Selwyn) (2010)

- Changing Education Paradigms - RSA Animate (Sir Ken Robinson) (2010)

- Mehr als 0 und 1 - Schule in einer digitalisierten Welt (Beat Döbeli Honegger) (2016)

Biblionetz-History

Biblionetz-History